Writer and director Nick Lane discusses Blackeyed Theatres latest production Jekyll & Hyde. Jekyll and Hyde it at the Connaught Theatre Thursday 4 – Saturday 6 November 2021. Tickets are available online or you can call the Box Office on 01903 206206.

Tell us about your new production of The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde…

Well, it’s a small/mid-scale tour of an adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic horror story but I’ve tried to put a twist on it. I was aware approaching the adaptation that people have certain preconceptions about the story, and I thought it might be fun to come up with something a bit different.

What inspired you to tackle this story?

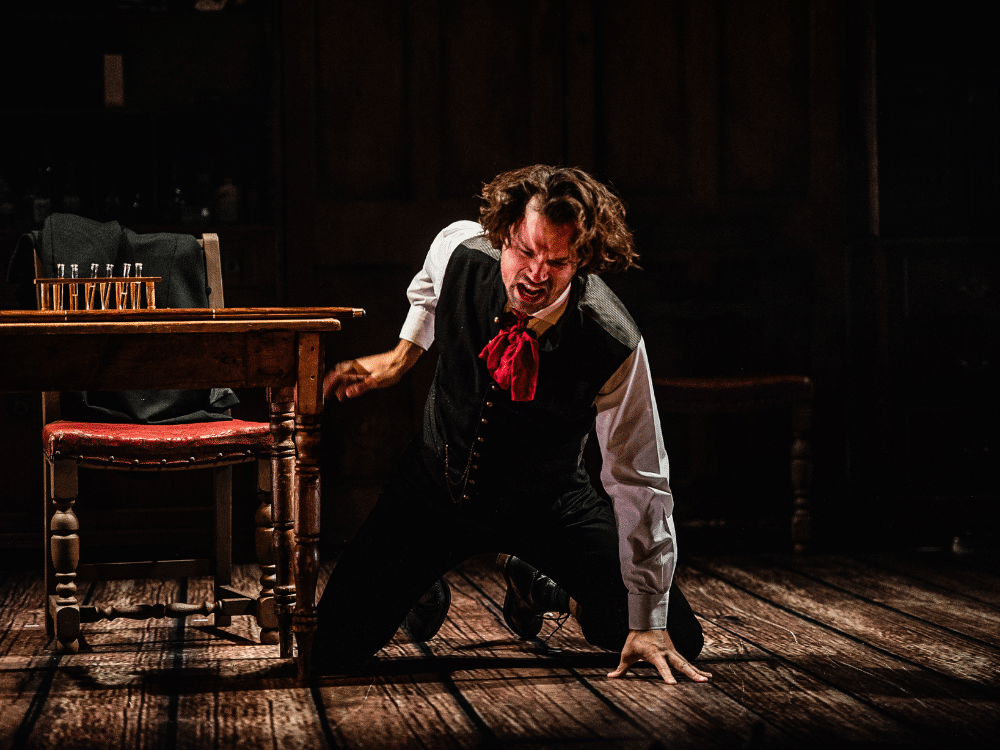

I think the story itself, the original tale; it’s just brilliant. And after that, with the other adaptations that I’ve done, what’s always helped me to get into a story is finding a personal angle – in terms of Jekyll & Hyde, what intrigued me was looking at what the consequences would be if Jekyll was incredibly intelligent but physically weak, and Hyde was a really powerful man, albeit very cruel.

Some years ago I was in a car accident that permanently damaged my neck and back. I wondered, if someone offered me a potion that was guaranteed to make me feel the way I did before the accident, but with the side effect that I’d become ruthless and horrible – would I drink it? Would I make that trade? If I knew I could do it for a day then I suppose I might, but what if the feeling of being strong and healthy became an addiction?

It’s Pandora’s Box. You know the risks of something but would you do it? A butterfly wouldn’t want to become a caterpillar again because once it has wings it wants to fly. That’s the difference, as soon as you make Hyde the strong one, I wonder if he’d want to go back to being weak old Jekyll again. So it’s a question of “does the body rule the mind, or does the mind rule the body?”

What’s different about this production?

I suppose if you were to describe the original novel as a traditional horror story, this is an attempt to find a new way to scare the audience. It’s a small cast, so I’ve tried to ramp up the physicality, the claustrophobia and the menace. And ultimately I’d like the audience to go home with the questions facing Jekyll racing around in their minds.

How have you approached this adaptation?

Jekyll is a medical man, so I’ve gone down the route of looking at why Jekyll is exploring the ability to split the mind. In the book, Jekyll is just fascinated by his own nature; he wants to look at why good is good and evil is evil within him. What I wondered was, what if Jekyll was looking at splitting the mind to perhaps find a cure for schizophrenia or any other mental disorder? You have to remain true to the source material and in particular the spirit, themes and drive that the author of the source material wants to explore. Beyond that, I guess you look for opportunities within the text to explore other things, and I find that question of research versus morality fascinating.

You’ve been keen to set the book in the era it was originally written in. Was that a conscious decision or did you not want to make a modern adaptation?

I think the themes are strong enough to transcend any particular period so I thought it was natural to stay faithful to Stevenson’s vision. There is a slight shift – Stevenson wrote the book in the 1880s, but doesn’t specify what years of the 19th century the story covers. This play is set in the 1890s, simply because at that time a lot of interesting historical events which I felt I could draw on were taking place. That particular era was also regarded by many as the birth of modern neuroscience so I’ve placed Jekyll amongst genuine experts in that field, as if he too were a pioneer – albeit a very twisted one with results that were more than he bargained for.

You mentioned you were keen to look at the back-story. What challenges does this bring to you as a writer?

Initially it’s down to the research and ensuring the story you’ve made is consistent. The book edition of Jekyll and Hyde that I have is only 48 pages long, although the print is very small! The original idea is absolutely brilliant, and at the time must have been chilling, but for a modern audience who aren’t surprised by the revelation that Jekyll and Hyde are one and the same, you have to work that bit harder to find something that might shock. Finding a good back-story actually presented me with a great opportunity to embellish the original text and add something that I hope Stevenson would approve of.

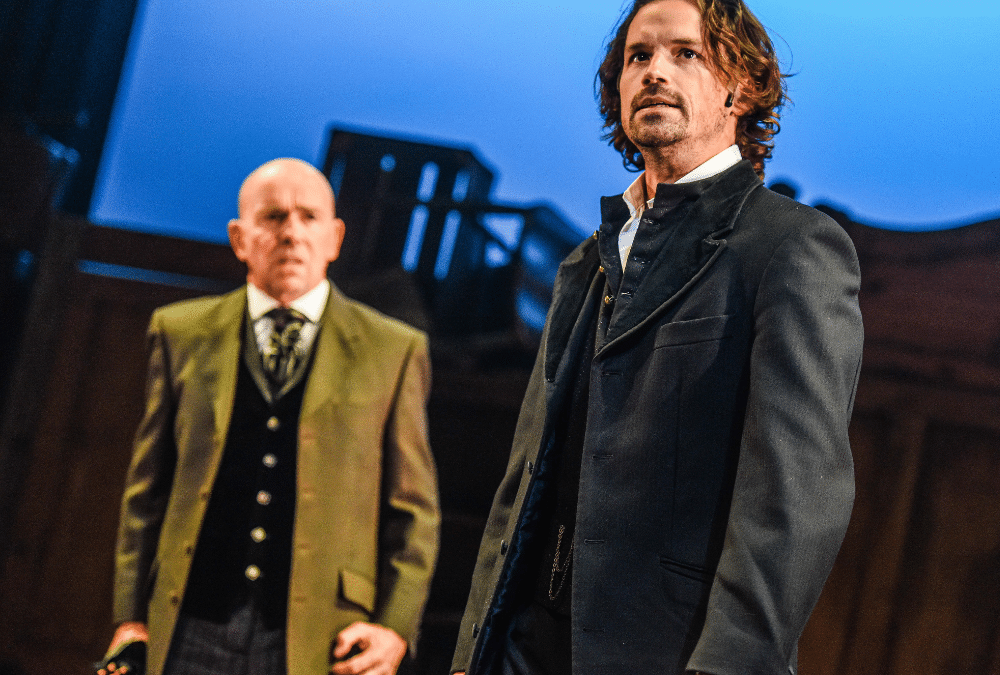

Within this production Jekyll and Hyde we see a lot of multi rolling – (sixteen characters are played by a cast of four). What made you decide to tell the story theatrically with a cast of just four?

It’s been my practice, my stock in trade, and Blackeyed Theatre has a tradition of telling stories with smaller casts. With a story like this it works really well. In the book Jekyll and Hyde are described as two different people, but generally adaptations have the same actor playing them.

There are stories you can’t tell with a small cast. I was given the option of what I wanted to adapt knowing the cast would be this size, so you have to find ways to tell those stories. I thought it would be nice to look at this story from a medical and philanthropic angle and to use multi-roling to our advantage because Jekyll and Hyde is the original multirole.

As a director how do you approach multi-roling with your actors?

There are lots of techniques, but the secret, if there is one, is to cast the right people who you know have got that skill. This piece is interesting as two actors play the same character, so we’ll have fun looking at gestures and vocal tone and body language.

I come at it from the point of view that if the words are there and actors are talented enough, I would rather give actors opportunity to explore and discover themselves what different characters are and we can discuss it. That gives actors ownership, rather than arriving with my preconceived ideas of what character are and make the actors conform to the way I work.

I approach it the way I would with a ‘one actor, one character’ play, which is to empower actors enough to feel strong enough to come to their own conclusions.

How important to this adaptation is the character of Eleanor and where did you draw inspiration for her character from?

I think all the characters are important, they lend focus to the wider narrative which I have decided to craft on. The novel doesn’t have a character called Eleanor; the women in the novel seem very functional at best. Stevenson was writing for a man’s world, his novels are very male dominated. Yet one of the biggest inspirations and motivators for his work was his wife. She pushed him to create; she was his harshest critic, his fiercest editor and his most strident advocate. I think that that’s in part where I got Eleanor from. Her character serves as a catalyst. She gives him a reason to continue.

There’s also Annie who is a prostitute character, who is very important for her socio political positioning. Eleanor is an Irish immigrant, so she is from the working classes, like Annie. We meet Eleanor, but she is outside her own class so we can use her as our eyes onto that world. Annie is still within the working classes. So for Eleanor, Annie is an example of ‘there but for the grace of God’ – had Eleanor made different choices, this is where she could have ended up. In terms of giving context to who Eleanor is, it’s really important to have Annie there.

Victorian society was deeply entrenched with the class system and lines were recognisably drawn. To have a working class character enter into that world, gives the audience a sense of that division.

In what ways do you hope this adaptation will appeal to a modern audience?

There will be physical theatre, movement and dance. There’s a new score being written by Tristan Parkes, who is a fantastic composer. And then four fantastic actors.

The first adaptation for stage took place less than a year after publication and 131 years later, the novel is still inspiring theatrical performances. What is it about the story that lends itself well to theatrical staging?

It’s a book with a number of very strong themes and a gripping mystery. There is room to put different characters in there. It’s a fun story to create onstage, because you can explode it. You can add to it while staying true to Stevenson’s narrative. I’m interested in why people do the things they do and the greying of morality. I enjoy creating well-rounded characters. For example Lanyon, in order to give a scale of morality. Utterson is black and white, the law. Jekyll is the greying morality – very morally flexible, Hyde creates his own moral universe and does as he wants. Lanyon is heart and conscience. And Eleanor is drawn to Jekyll and Hyde because for a certain type of person, sometimes good, moral people like Lanyon can be perceived as dull.

Another thing I wanted to do was look at a different reason behind why Jekyll is so insistent on pursuing this particular line of research. I think that’s why the story has persevered. It gives writers scope and opportunity to play and explore with a really strong narrative core.

Jekyll and Hyde it at the Connaught Theatre Thursday 4 – Saturday 6 November 2021. Tickets are available online or you can call the Box Office on 01903 206206.